Nobody should take Larry Flynt for granted.

After all, the man who was once dismissed as an underdog when he started Hustler magazine, gambled hard and smart and came out the winner — big-time.

As we usher in a new decade, XBIZ is celebrating the storied life and unflagging advocacy of this heavyweight champion and toasting to his leadership and visionary status in an often misunderstood industry.

Mr. Flynt — that’s what his staff calls him — received us in his office, located in the penthouse of an iconic Beverly Hills office building. The landmark is colloquially known as “the Hustler building,” but the sign above it reads LFP, short for “Larry Flynt Publications.”

Mr. Flynt owned this 10-story building from 1994 until 2013. He bought it for $19 million and sold it for $89 million to a real-estate investment trust, while retaining the use of several floors as a tenant.

“We’ve been able to unlock significant equity, which we can now put to much better use in other ventures and achieve greater returns,” he told the press at the time of the sale.

A few months before the sale, he told the Hollywood Reporter that he would put the tidy profit “toward buying another casino or another operation that would fit with my broadcasting entities.”

The gambling, retail and broadcasting operations of the Hustler empire are thriving, and its men’s magazines — Taboo, Barely Legal and the crown jewel, Hustler — have doggedly survived the Great Print Bloodbath of the new millennium.

The magazines survived because Mr. Flynt is passionate about publishing and still works hard at tailoring them just to his taste, never wavering from a formula of anti-authoritarian irreverence, naked pictorials and earthy humor.

Oscar nominee Woody Harrelson played Mr. Flynt in the 1996 film “The People vs. Larry Flynt.” Mr. Flynt appears briefly in the movie as a stern judge who condemns Harrelson-as-Flynt. To this day, he keeps in his office a backstage shot of that scene, which Harrelson autographed “Larry — Can’t believe you sentenced me to 25 years. Love ya, man — Woody.”

“I had so much fun, I’m going into the [movie] business,” Mr. Flynt told a magazine in 1996, when the movie was released.

The film is now almost 24 years old, which means many of the girls featured in Hustler, Taboo and — most definitely — Barely Legal today were not born when it came out.

Adult performers still know the Hustler brand, though. Chances are they grew up at spitting distance from one of Mr. Flynt’s popular Hustler stores — well-lit, female-friendly (by design) emporiums of all things sexy.

The retail chain, currently expanding throughout the country, particularly the South and the Midwest, is officially branded as “Hustler Hollywood,” promoted as “a leader in cultivating an upscale, sexy shopping experience.”

Mr. Flynt still holds weekly all-hands-on-deck meetings in a lavish, red-walled boardroom down the hall from his Beverly Hills penthouse office, to go over all aspects of his enterprise. An enormous photo portrait, often mistaken for an oil painting, of Althea Leasure, his fourth wife and a crucial figure in his life and in the story of Hustler, hangs in the room where the department heads sit to discuss business.

Behind where Mr. Flynt sits during the weekly meetings there used to be artwork on the wall, but he had it replaced by a map of the United States with an elaborate system of flag pins tracking the expansion of the Hustler Hollywood store chain.

“Some of them are properties or markets we are actively looking at,” explains a staff member in hushed tones.

In describing the industrious spirit Mr. Flynt so aptly embodies, Susan Colvin of CalExotics, who has known and admired him for 25 years, says, “Even today, he goes to his office every single day, and he’s 100 percent hands-on in his business. He’s gone to city council meetings, personally, to explain his business and argue his stores and casinos should be there.”

While he has just turned 77, people sometimes think he is older because he attained fame at a young age, yet he has been a recognizable name and face since 1975.

Mr. Flynt is over six feet tall. Photographs taken immediately before the assassination attempt show him towering over journalists in a dapper three-piece suit, lecturing them in a fiery style, on the stump, on freedom of speech and his beloved First Amendment.

When Mr. Flynt speaks these days, one can be lulled by his laconic delivery into thinking that age and endless treatments for a catalog of ailments, both related to that devastating day in Georgia and not, have taken their toll.

“Bullshit,” as he would undoubtedly say.

In fact, when one plays back a recording of an interview, his words and their intent are crystal-clear. One can gather a lot of business and life wisdom from them.

“Larry did not change over the years,” says Doc Johnson founder Ron Braverman, a long-time friend. “Larry is really the person who’s responsible for the modern day adult business, and it’s his leadership that has brought it into today’s mainstream world.”

There is a linear, coherent pattern in the decades-long defense of personal liberties in a country this iconoclast truly, unironically, loves.

“This country is pretty corrupt,” Mr. Flynt tells XBIZ, and his thoughts trail. He is unusually reflective when being interviewed about his story and about deeper subjects. His Southern drawl allows him to weigh every word. This is in contrast to when he pauses the interview to pick up a business call. He’s quick and direct when dealing with the day-to-day of his operations.

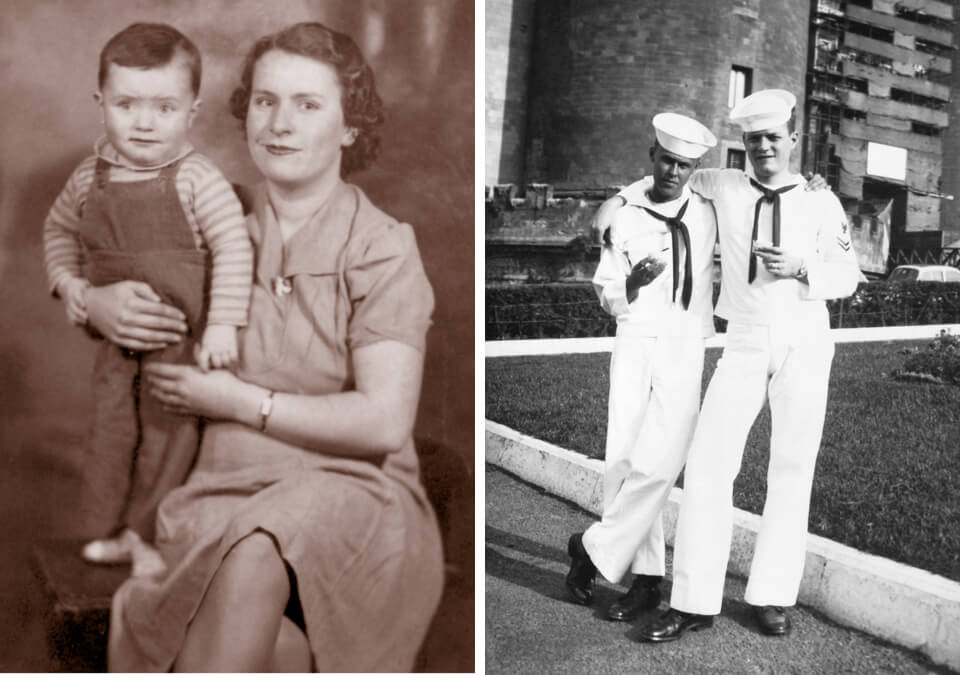

A third way Mr. Flynt speaks is what his associates immediately recognize as “the glint in the eye” mode — right before he’s about to make a deadpan joke, or say something off-color, or tell a story in which one of his pranks or stunts got a rise out of some stuffy character. In this third mode, his eyes brighten up and his spirit shines through. It’s a glint that is there in the earliest photos of him as a young kid, when he changed addresses often between his divorced parents and other relatives in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio. It’s there in his Navy pictures.

And it’s most certainly there in those working class clubs of Dayton and Columbus where his fortune began to rise, long before he was “Mr. Flynt,” long before the Beverly Hills penthouse office crammed with his art collection, an idiosyncratic combination of 19th century figurative paintings and sculptures with a smattering of Art Deco figurines.

Mr. Flynt’s gaze turns somber. “This country is pretty corrupt,” he says again.

Isn’t he an idealist, though, thinking his beloved First Amendment is the ultimate protective shield and writing editorials every single month about the country’s political future and what politicians should do to be better?

Cue the glint in his eye.

Yup, rabble-rouser Larry Claxton Flynt, Jr. from Magoffin County, Kentucky is still in there, always ready for one more round in The Fight, unstoppable in spite of all the efforts of moralists, hypocrites and would-be assassins.

“I guess at heart I’m an anarchist,” he says, quietly chuckling.

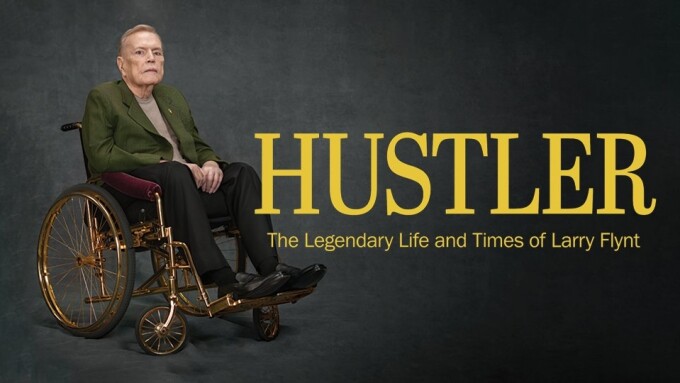

We met with Mr. Flynt in his office three times for this story, unprecedented for the trade press. After the third interview, he participated in the conceptual photoshoot that serves as the cover for this special tribute issue.

“To the left a little bit, Mr. Flynt. Show us a smile. Now look like a badass!” instructs the photographer.

He poses like a man who’s been used to being photographed for decades: like a total pro.

As the photographers wrapped up, his refrigerator-sized, impeccably besuited bodyguard positions Mr. Flynt behind his desk.

“How are the stores doing?” asks Alec Helmy, publisher of XBIZ, who had dropped by the shoot to salute his legendary friend.

Mr. Flynt’s eyes light up at the mention of the Hustler Hollywood stores. His Southern drawl becomes animated, excited about the prospects for 2020.

“Right now, we’re just looking for good stores. Good locations,” he tells Helmy. “You’ll have zoning issues sometimes. We fight it. We have to. We win some, we lose some. You can’t zone out the First Amendment.”

Determined to Succeed

Larry Flynt was born in the Kentucky hills. His parents divorced when he was nine and he spent his pre-teen and high school years between Kentucky and Indiana, bouncing around between his mother, his father and his maternal grandmother.

When shown a picture of those hills near his birthplace of Lakeville, Flynt does not look at it with anything resembling nostalgia.

“It [just] looks like the area down there, you know?” he says. “That could be any place in Kentucky.”

“It was where I was born and where I started out,” he continues. “And the sooner that I could get out of there the better it was for me. I didn’t lose anything there.”

Growing up in the impoverished area right between the historical divide between the North and the South, he recalls thinking that “there had to be a lot more to life than what was available to me.”

“You gotta remember, I was born dirt-poor. To me, I thought that was how you measure success: by what you have been able to achieve. So that’s what I focused on. There wasn’t much of a way to make a living in Kentucky.”

According to Flynt, not even the local coal industry was thriving when he first needed to make a living.

“The biggest industry in Kentucky was jury duty,” he chuckles, in an often-repeated quip.

However, look closely at the shelves where Flynt keeps his trophies and accolades, for his First Amendment advocacy and for his achievements within the adult industry — including an Industry Icon Award bestowed by XBIZ in 2012 — and you’ll find a plaque from his birth county acknowledging his charity work there.

Mr. Flynt loves to tell the story of how, as a teenager, he escaped Kentucky, and formal schooling, by talking his way into the Army and then the Navy while still underage.

In July 1964, at age 21, he was honorably discharged from the Navy and moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he had lived before enlisting.

“There was more ways to make money in Ohio, there was more industry up there,” Mr. Flynt tells XBIZ. “You couldn’t make a living in Kentucky, but you could make a living in Ohio.”

At the time, he was a voracious reader of self-improvement books, like Napoleon Hill’s “Think and Grow Rich,” a classic of the genre originally published in 1937, but still very popular in the ‘60s.

He started working at Inland Manufacturing doing what he describes as “a mind-numbing job” on the assembly line.

Instead, what Flynt wanted was to work for himself.

So, he started taking all the overtime he could get and took a second job at Chrysler Airtemp. He was on a mission.

Young Entrepreneur

Larry Flynt was now in his early twenties and, like many working-class men of the time, was a veteran. He also had an ex-wife and child support payments.

After the collapse of his marriage, a newly single Flynt meditated on a key passage in “Think and Grow Rich.” The author argued that the “energy required to be successful was the same force that went into courtship and sex.”

According to the book’s theories, young men typically waste the best years of their lives “trying to impress women rather than channeling their energy into successful business ventures.”

The 22-year-old took this to mean not that he should avoid sex, but that he should “dispense with the romantic element of it — the emotionally risky part.”

Flynt’s first business decision with the money he had accumulated from his “mind-numbing” gig was putting down $1,800 in early 1965 as a down payment for his mother’s Dayton bar, the Keewee. He agreed to buy it from her for $6,000 and kept her on payroll.

His reasoning for the purchase was simple. “I love women and I love sex,” he once famously said. “Who gets laid the most without having to make a long-term commitment? Bartenders, entertainers and club owners. They don’t have to be the most handsome or articulate; they’re just around women all the time. They have the most opportunity.”

But Flynt quickly also discovered that, in his words, he “had a gift not only for the consumption of alcohol, but for the selling of it.”

The budding nightlife entrepreneur’s trump card was his knack for thinking up gimmicks and stunts to dress up the business of selling booze.

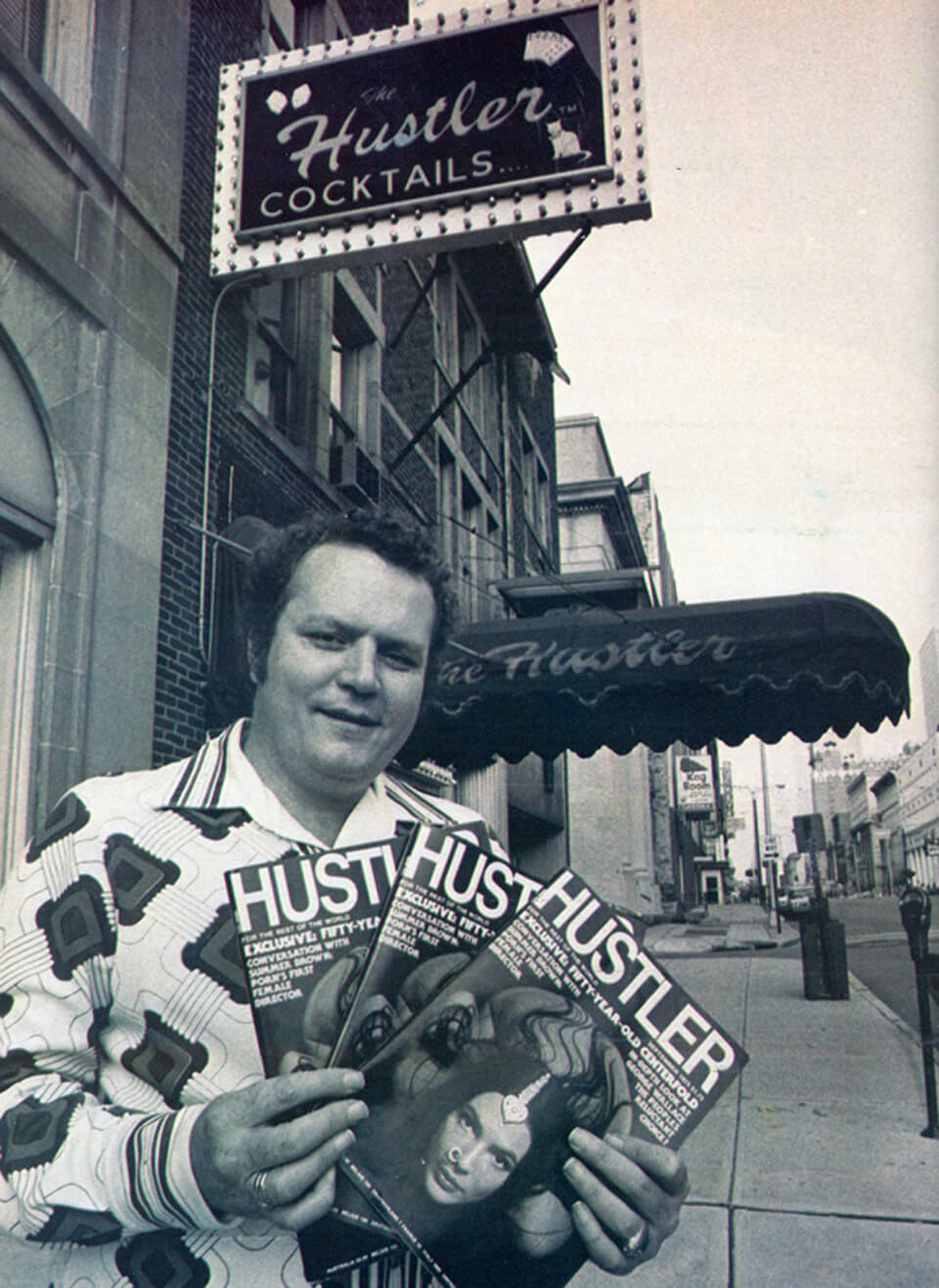

“I always felt when you’re trying to promote yourself,” he tells XBIZ, “you need to do something outrageous, you know. The first bar I owned in Dayton, Ohio only had a beer license. I didn’t have a liquor license. I needed something to promote it. When I took it over it was selling maybe three cases of beer all week; after I’d been there for three months it was selling maybe 3,000 cases of beer a weekend.”

What caused this turning point? “The bar was in an old house that had a backyard and there were a couple of picnic tables out there,” he reminisces. “So I put in a couple of horseshoe stakes and we would have horseshoe tournaments there on Sundays and people would come from miles around and play. And that was something that took off for me. That’s the only place in the city where you could be involved in a tournament. This kind of crazy, off-the-wall stuff, you get people caught up in.”

This was an important self-taught business lesson that Flynt still champions to this day: know your customer.

Flynt has described those Keewee patrons as “working-class people like myself, especially hillbillies.” He calls this crowd, without judgment, “hicks” originally from Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia. So the Keewee sign came down. The bar was now Hillbilly Heaven.

Flynt wanted his customers to feel at home. And they did. By the end of the summer, Hillbilly Heaven was turning a profit.

He then added a second Dayton joint to his portfolio, naming it Larry’s Hangover Tavern, followed by a third, The Factory. Now, workers from the nearby General Motors and National Cash Register plants, could now go from the factory to The Factory.

The bars needed music — country music — and that’s how Flynt became interested in the lucrative jukebox business, and its close cousin, the pinball machine. The nickels and dimes, he noticed, added up to some serious coin. So he founded the National Vending Machine Company and added it to his club enterprise. The name was fanciful: Flynt’s “national” scope at the time was limited to Dayton, Ohio.

With this passive income accumulating, and with Flynt growing tired of the endless bar fights at the joints he ran, he attempted to diversify to a more upscale clientele. So, shortly before 1968, he bought a bar on Main Street and called it Whatever’s Right.

The ‘60s were in full swing, and Flynt, 25 at the time, was going to be a nightlife entrepreneur, Dayton’s own answer to Hugh Hefner, who was already renowned for the Playboy Clubs – which Hefner cleverly advertised through jazzy, hipster TV shows.

The Hustler Clubs

During this period, Flynt started thinking about adding “hostesses who danced,” and the move proved successful. He then heard about the “go-go club” craze going on around the world, so Flynt imported the concept to Ohio. The go-go girls, often in cages, danced in bikinis.

Flynt initially thought that he should call the new go-go club The Hooker. A minute later — literally — he had come up with a better name: The Hustler Club.

When Flynt first envisioned the theme for Dayton’s Hustler Club, he was thinking along the lines of mobsters, with framed pictures of a rogues’ gallery over the hand-carved wooden bar. To this end, one night, Flynt and a vice squad cop who frequented the club shot bullet holes through the portraits.

One of the first press clips about the newly opened club concerns Flynt paying back a bank loan for remodeling the place.

Harkening back to that time, Mr. Flynt showed XBIZ a black-and-white local newspaper picture of himself in 1968 paying back the loan — in pennies. He chuckles. “I owed the bank some money and they were pissed off at me. Paid them back in pennies, yeah. I figured it would piss them off.” He smiles with that signature Flynt glint in his eye.

In late 1968, he sold off the two “hillbilly” joints to focus on the upscale Hustler Club and his National Vending Machine Company operation. He also opened a second upscale go-go venue, which he called Talk of the Town.

The two Dayton clubs were doing great business even if the beer was wildly overpriced. This puzzled some of Flynt’s distributors and competitors.

“I’m selling pussy by the glass,” he would answer, “and my customers don’t care about the price of drinks.”

To keep the operation legit, though, Flynt had to prevent the venues from being perceived as “hooker hangouts.” He insisted on hiring only “wholesome-looking girls.”

Here was the Hustler Club philosophy, based on Flynt’s understanding of male psychology: “I wanted to serve the solitary businessman who would otherwise be sitting in a hotel room, staring at four walls and watching Johnny Carson. They were lonely. They wanted a woman, and if she was pretty, all the better! I carefully instructed my hostesses to pay special attention to the guy who was getting a little older and fatter, the one who smelled of cigar smoke. No girl would look twice at him in another club. That kind of guy had money, maybe even an expense account. I told the girls, when talking to a customer, they must never complain and absolutely never nag. These guys got enough at home.”

Even in 2019, Mr. Flynt retains this philosophy. “I started out in the bar and club business,” he tells XBIZ, “and I’ve always been involved in sex one way or another. When I was in the bar business, I always looked at it as ‘selling sex by the drink.’” He smiles. “Selling the sizzle and not the steak.”

Running a self-described “tight ship” in the manner he had been taught in the Navy, Flynt began expanding his operation beyond the confines of Dayton, branching out into other Ohio cities such as Cincinnati, Columbus, Cleveland, Toledo and Akron.

From 1968 to 1973, Flynt secured his position as a nightclub kingpin. By the time he started to think about branching out into publishing, he owned eight Hustler Clubs and had 300 employees. The clubs were clearing upwards of $100,000 a year (equal to about half a million dollars today). At 31, being a literal millionaire suddenly did not seem out of reach for Flynt. He had a fleet of limos and enjoyed being photographed in them, right next to their futuristic-looking portable color TVs.

But the other leg of Flynt’s midwestern enterprise was faltering – the National Vending Machine Company went into the red and funds from Hustler Clubs were being diverted to get it out of the hole.

Hustler Magazine

In 1968, Flynt bought the Dayton franchise for a Phoenix tabloid newspaper called Bachelor’s Beat and started using his clubs’ go-go dancers as cover models. This angered the moral sensibilities of many Ohioans and Flynt faced an uphill battle to get his racks on the streets.

Fast forward four years and the Bachelor’s Beat experiment had morphed into a newsletter called The Hustler, which promoted his eight go-go clubs.

After a series of false starts with distributors and partners, in the spring of 1974, Flynt partnered with publishing industry veteran Ron Fenton, who had founded the men’s magazine Gallery. Flynt agreed to finance a new national magazine.

“What I had was cash flow,” he once remarked, “and I could either use it to chip away at my debts — for the rest of my natural life — or risk it on a new venture that held out the possibility of making a complete recovery. It was an easy choice. The fact that I knew next to nothing about publishing didn’t faze me. I’ve never been risk-averse.”

Flynt has stated that he vaguely remembers seeing a copy of Playboy once before 1974 and he had never seen Penthouse. He went to a newsstand, picked up a copy of each and studied them.

He quickly decided that their editorial content was the same as mainstream magazines and therefore irrelevant. As for the photos, both publications, he thought, made the implicit assumption that men were turned on by women with big breasts, great butts, nice legs and perfect faces. While he didn’t disagree with that notion, Flynt thought the working-class men he knew best — from Kentucky, from the Navy, from Hillbilly Heaven, all those truckers that would deliver his new magazine to gas stations all around the country — were turned on the most “by female genitalia.”

“If someone,” he thought, “published a magazine more attuned to what the average Joe really liked, a whole new market could be created.”

According to Flynt, the magazine distributor wanted to call it Pleasure. The distributor told Flynt that “‘Hustler’ had connotations. You know, it sounds like somebody ‘hustling’ somebody else, or maybe a magazine about hookers.”

Flynt threatened to withdraw his investment unless he got the name he wanted.

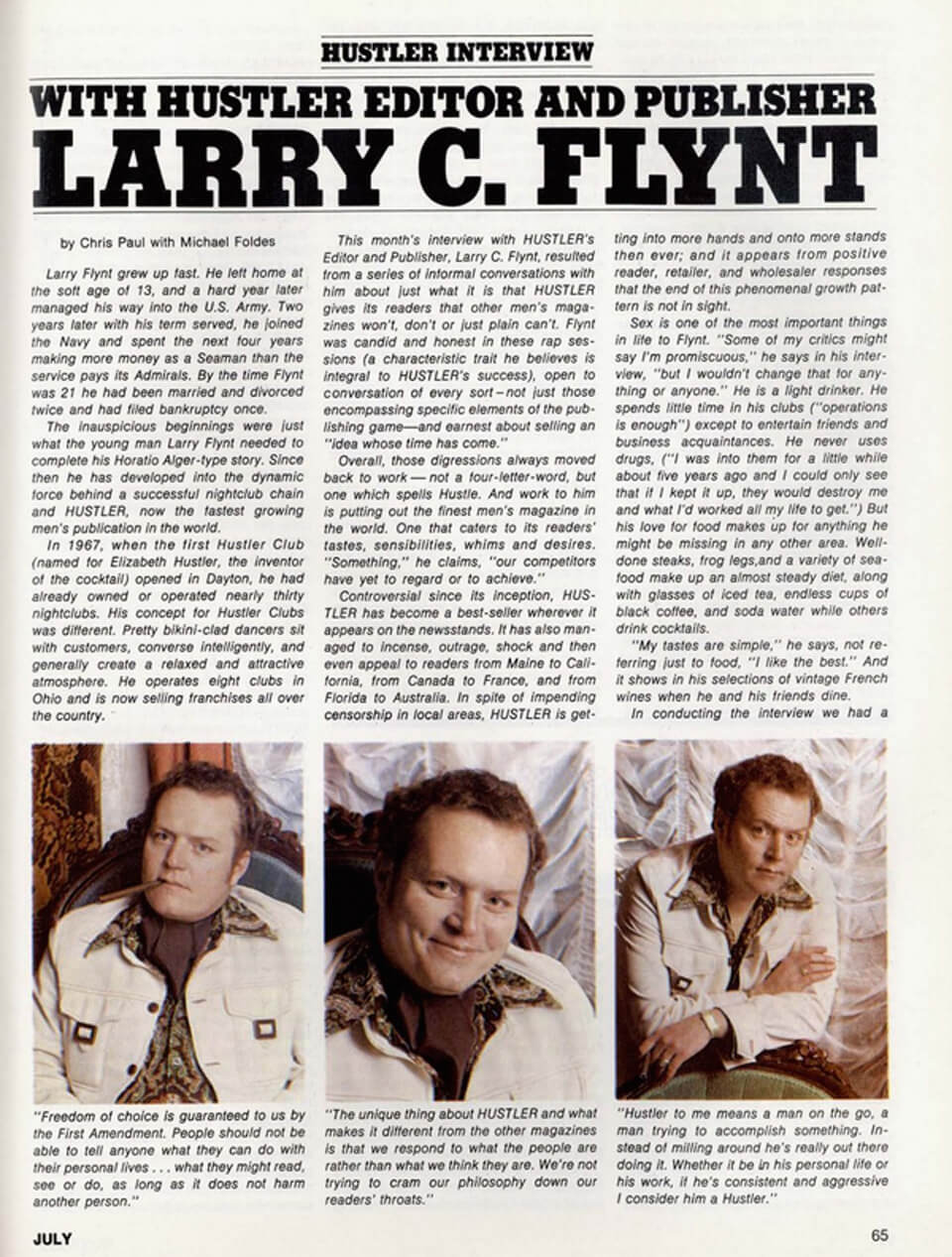

The first issue of Hustler came out in July 1974.

The distributor told him he’d have to front the investment for six issues, or up to $500,000, before realizing a profit. The magazine would have to survive through the year or Flynt and his businesses would be toast.

Flynt himself was not impressed by how the first issue of Hustler turned out. In his memoir he describes it as “hastily assembled,” looking “like a high school version of Playboy with a little Penthouse thrown in.”

A columnist for Al Goldstein’s New York-based Screw magazine joked that Hustler “[edged] out Refrigerator Monthly for most boring magazine in America.”

Flynt read the Screw review and agreed with the sentiment. His co-publisher, the seasoned publishing vet Ron Fenton, bailed out after the first issue. But Flynt had no backup plan. Hustler had to succeed, at least until 1975.

So, he picked up the phone and called Al Goldstein and asked about the guy who had written the Refrigerator Monthly pan. It was Bruce David. Flynt hired him as Managing Editor to turn the magazine around, fast.

Goldstein proved to be a source of inspiration for Flynt and even took the young publisher under his wing. Goldstein’s philosophy was that “the American libido was still firmly chained in its backyard, hidden from company as if it were a cretinous child. People were still coy talking about sex in public.”

By issue No. 5, Flynt had figured out how he wanted to differentiate his Hustler models from the competition. He thought Hefner had always talked about “the girl next door,” but that Playboy models were unattainable superwomen. Hustler, he determined, would literally feature “the girl next door” by advertising in Ohio newspapers for nude models.

The response was overwhelming, and suddenly Hustler’s photographers were giving the 1970s soft-focus treatment to a variety of local beauties for $500 a pop (versus Playboy’s $1,500 and $3,000 for centerfolds).

“These women,” Flynt has said, “ranged from tall to short, were blonde and brunette, large-breasted and small-breasted.” Hustler published models in their 50s, trans models, plus-size models, pregnant models and women of all ethnicities more regularly than — and often long before — its competitors.

As for the editorial content, again, Flynt returned to the working-class Joes he knew best. “I wanted to provide a forum for the kind of dark humor that characterized the mills, factories and workplaces of ordinary people.”

Playboy could keep its high-end stereo reviews and cocktail-of-the-month recommendations. Hustler was going to be, as the cover proudly declared “for the rest of the world.”

A Cultural Phenomenon

The November 1974 issue marked the moment Hustler became a cultural phenomenon.

Now under the oversight of a more professional team and with Flynt having learned the publisher ropes on the go, it was time to enter the big game. Penthouse had briefly challenged Playboy’s supremacy in 1969 by nationally distributing a men’s magazine that showed pubic hair.

Doc Johnson’s Ron Braverman reminisces about those early Hustler days.

“It was a time [when] most people did not think ‘out of the box,’” Braverman explains. “Even back then, Larry was a force to be reckoned with. It was his attitude, it was his words, it was him being willing to stand up for what he believes. It was his whole attitude.”

The November 1974 issue of Hustler moved the nudity goalposts to the point of no return with a “pink shot” showing a full-on vagina, in Flynt’s own words, “open like a flowering rose, fragile and pink.”

The slogan got an update: “Hustler Magazine. For the rest of the world. Hardcore since ’74.”

By going into uncharted territory, Flynt was courting trouble and trouble was what he got. Forty percent of his wholesalers refused to carry it, making it essentially banned in whole territories like Canada. Still, it sold out.

By April 1975, Hustler magazine was making a lot of money and now floating the burgeoning Flynt empire. He even began planning his retreat from what he called “the bar business.”

As the magazine was on its initial upswing, Flynt hit major paydirt: an Italian paparazzo offered him photos of President John F. Kennedy’s widow, Jackie Onassis on a nude beach. The pictures had been taken in Greece years before and the paparazzo had sold them to an Italian men’s magazine in 1972, but nobody in America was willing to touch them.

Flynt jumped at the chance, guided by his killer instinct for a gimmick. He bought the photos for $18,000 and ran four of them, full-page, in the August 1975 issue. The Ohio-based monthly suddenly became an international sensation.

Time and Newsweek wrote about it. Much to the surprise of the mainstream press, women accounted for many of the purchases. They had a field day with accounts of “little old ladies” buying Hustler at newsstands and gas stations throughout the country.

And then the governor of Ohio himself was caught buying a copy of the August issue, which he explained he had purchased for “scholarship” purposes.

The Jackie Onassis photos were the gift that kept on giving. Flynt endlessly republished them in Hustler compilations and even printed posters of the nude First Lady photos, which he sold for years through ads in Hustler.

By the end of 1975, the Wall Street Journal declared that Hustler was “not only the fastest-growing men’s magazine around, but one of the fastest-growing magazines of any kind, ever.”

Larry Flynt had become a millionaire.

In 1976, the 33-year-old moved into his first bona-fide mansion in the conservative Columbus neighborhood of Bexley. He brought along the woman, nine years his junior, who had become his main personal and professional partner, Althea Leasure.

Flynt and Leasure had met in 1971. She was one of his Hustler Club hostesses, but soon started accumulating trust and authority under him. They became romantically involved, even as Flynt was pursuing other women.

She became a trusted part of his organization and in 1975, he named her Executive Director of the magazine. She also acted as gatekeeper to the owner and publisher. The next year Leasure became his fourth wife.

Obscenity Challenge

1975 was the year of Saturday Night Live and the Gerald Ford presidency. If Hefner projected the aspirations of the 1950s urban middle-class and Bob Guccione was a more freewheeling, 1960s spirit, only someone like Larry Flynt could have exploded into the national consciousness during the 1970s.

In Hustler, Flynt started penning monthly essays about what he felt were preposterous obscenity and sexual behavior laws. And he started paying a price almost immediately. “There was hardcore pornography everywhere,” he has said, “in adult bookstores and magazine stalls, and behind newsstand counters. It eventually dawned on me that the reason I was singled out was the political and social content of the magazine.”

The first serious legal challenge came in the form of charges of pandering, obscenity and “organized crime,” filed against the entire Hustler masthead in Cincinnati during the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations.

The prosecution had been inspired by a religiously motivated lobby called Citizens for Decency Through Law, spearheaded by the Catholic businessman Charles Keating, who would be convicted in the early 1990s — to much Flyntian glee — on federal and state charges of fraud, racketeering and conspiracy for his role in the ‘80s Savings & Loan Scandal.

“Before he fucked the savings and loan industry, Keating tried to prevent the portrayal of fucking in magazines,” Flynt once quipped.

The establishment in Cincinnati were ultra-conservative Catholics and Flynt took to the streets, not for the last time, to fight them. He started an organization called Ohioans for a Free Press and held a rally.

“We’re talking about the censorship of a magazine with three million circulation, sold in 25 different countries with an estimated 15 million readers,” a fire-and-brimstone spewing Flynt laid down. “That’s 15 million voices that have a right to be heard. Now either we have a free press or we don’t. I think that if we do have a free press, it’s time that the goddamn journalists in this country got some backbone.”

“One of the greatest things that we have as American citizens, goddammit, is the right to be left alone,” Flynt concluded. “And me and my readers deserve that right.”

Longtime industry business owner Kenny Guarino recalls to XBIZ, “Larry was never afraid to push the envelope. He was fearless in his work and his belief that, although at the time what he was publishing was not universally accepted, it was legal. It is this integrity and determination that has made him a leader among his peers.”

Susan Colvin of CalExotics echoes those sentiments. “Larry will not take ‘no’ for an answer,” she tells XBIZ. “Whether it’s a city or a judge, he’ll put himself personally in danger for what he thinks is right. No is not in his vocabulary. It’s hard to find people who’d do that. It takes a lot of fortitude and self-confidence.”

During the Cincinnati trial, the deck was stacked against Flynt and his charged editors. Keating’s Citizens for Decency Through Law was operating in tandem with prosecutor Simon Leis Jr., who told the jury in his summation that “sex is a beautiful thing — there’s no question about it — but only in the proper environment.”

Then he took a piece of chalk out of his pocket, dragged it across the courtroom floor and said “It’s time to draw the line against obscenity.”

Representing Flynt was First Amendment expert Herald Fehringer and his young associate, Paul Cambria.

“I first met Larry a year before,” Cambria recalled to XBIZ. “I had just started out and I was with Herald Fehringer, who had a huge reputation in the First Amendment area.”

“Herald and I had just finished representing Al Goldstein and Screw magazine in Kansas City and we won the case. And one afternoon I got a call here in Buffalo.”

Cambria still recalls that first conversation: “My name is Larry Flynt and I’m publishing a new magazine called Hustler,” to which he retorted, “Never heard of it.”

“Well, I want to interview you and Herald for my magazine,” Flynt said, explaining how he had heard about the Screw verdict. Cambria was flattered, and Flynt, the consummate salesman, revealed the reason for the call. “Say, do you only do obscenity work?”

“Actually, most of the time we don’t,” Cambria replied, “we are traditional criminal lawyers,” prompting Flynt to explain he had some other charges in Cincinnati and he needed a lawyer.

Cambria was charmed by Flynt’s entertaining chutzpah, so he informed the young publisher that his firm would need a $5,000 retainer (in 1970s money). Flynt said he couldn’t make the payment in a lump, but could send it in installments.

“There was something about the guy that just clicked with me,” Cambria reflects.

Cambria recalls telling Fehringer about their new client. “You got us going to Cincinnati on the cuff, with no retainer?” he retorted. But they took the case anyway.

“[Simon] Leis had been after Larry for some time,” Cambria tells XBIZ. “At some point he used to have the girls dance in the front window of the Hustler Club in bikinis. The city told him to cut it out because it was a live display. So Larry set up a closed-circuit camera and a TV behind the window that showed the girls dancing.”

“We knew that the ‘organized crime’ statute was ridiculous,” explained Cambria. “Five or more people to commit any offense for gain and you could get up to 25 years. Five kids steal apples? That was ‘organized crime.’”

The other defendants were acquitted. Flynt was convicted on all charges and dragged in handcuffs in front of Judge Morrissey.

“The judge said, ‘Step up here Mr. Flynt and we’re gonna sentence you right now,’” Cambria remembers to this day, laughing.

“Do you have anything to say before I pronounce sentence?,” asked the judge.

“Yes, I do. You have not made an intelligent decision in this case and I don’t expect that now,” Flynt spat back.

“$11,000 in fines and 7-to-25, no bond!” sentenced Judge Morrissey, exactly as played by Mr. Flynt himself in his Hollywood biopic.

“Is that all you got?” Flynt responded.

“That’s the maximum sentence,” said the judge.

“I loved it,” Cambria recalls to XBIZ. “How can a young lawyer not love all this action? The New York Times, Harold Robbins, everyone was there in Cincinnati.”

As for the quips and provocation, Cambria is sure Flynt had thought about it before the hearing.

“Larry has a lot of good one-liners,” Cambria explains.

Flynt served six days, speaking to the national press throughout, and was released pending appeal. The charges were overturned in 1979. The statute was found to be unconstitutional. It was struck down and the cases were vacated.

Flynt’s animosity towards his Ohio accusers did not subside over time. Something “that always infuriated me,” he said in a 2014 interview, “is do-gooders like Keating. They couldn’t keep the streets clean, but they wanted to keep your minds pure. I was aggravated by that. I never felt that the government should be in the business of dictating morality.”

Religious Conversion

The Cincinnati trial made Larry Flynt famous nationwide. “He was on the talk shows, the subject of all kinds of political cartoons,” Cambria tells XBIZ.

However, during the appeals process for the Cincinnati obscenity conviction, Larry Flynt became an unlikely convert to Christianity.

A month before the start of the Cincinnati trial, Democrat Jimmy Carter, a deeply religious man of liberal convictions, had been sworn in as president. His sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, had summoned the legally troubled Ohio pornographer to discuss sex and religion and the two had struck an unlikely friendship.

Ruth Carter was an evangelist and the two had become close, to the point that Flynt invited her to fly to California in his “vulva-pink private jet.” Somewhere above the Rockies, something happened to Flynt and he had a religious vision of a bearded figure, God, the apostle Paul and the late comedian Lenny Bruce.

“I don’t know if it was some chemical imbalance in my brain, a symptom of the stress I was under, or a manic depressive episode,” Flynt reflected years later. “It was powerful.”

When they landed in Los Angeles, Flynt called Leasure and told her he had found God.

Flynt rang in 1978 a seemingly changed man — he had become a vegetarian, he insisted on raising everyone’s salary against the advice of his accountants and he quoted the Bible and was using the pages of Hustler to let everyone know about his conversion.

During his Christian conversion, the Hustler publisher became convinced that he couldn’t just focus his publication operation on smut.

This Christian period is at the root of the diversification of Larry Flynt Publications (LFP) into non-pornographic areas, which included at first some alternative weeklies — like Southern California calendar of hipness The Los Angeles Free Press — and later grew into a diverse portfolio.

During its heyday, LFP started or acquired a variety of mainstream titles including Maternity Fashion & Beauty, Code: The Style Magazine for Men of Color, Catalog Shopping in America, Camera & Darkroom, gaming magazine Tips & Tricks Codebook, Gen-X Spin-competitor Rage, and Big Brother, the iconic skateboarding magazine.

At one point Flynt’s magazine distribution company was one of the largest in the country, trucking around and depositing in newstands about 200 titles, including the New York Review of Books. He reportedly sold the distribution company in 1996 for $21 million.

The Assassination Attempt

In early 1978, another obscenity indictment popped up in Lawrenceville, Georgia, the home state of President Carter. This one was not unexpected.

“Larry thought he should be able to sell the magazines everywhere,” Cambria tells XBIZ.

According to the lawyer, the main newsstand operator in Atlanta, and in several airports, told Flynt that the operator “had been threatened by the local prosecutor that if he handled Hustler as opposed to all the other ones, that he was going to get arrested.”

In September 1977, Flynt rented a downtown Atlanta shop to deliberately challenge the local crackdown on Hustler and his various men’s magazine titles by selling copies himself.

While he was playing shopkeeper, a prosecutor from the neighboring county served Flynt with an arrest warrant.

“Hustler had been selling in Lawrenceville as well, so [the other prosecutor] accelerated his charges so they would come [before the Atlanta ones],” explains Cambria.

In March 1978, Cambria and Flynt went to Lawrenceville and they hired a local attorney named Gene Reeves.

“We paid him $500,” Cambria tells XBIZ. “He had been there for a long time and we wanted him to advise us on jury selection. Nice guy, older guy.”

“After we selected the jury, he said, ‘Do you mind if I stay around? I need to restart my practice and this would help.’ We said, ‘Sure! You can babysit Larry while we work during the lunch hour.”

On March 6, Flynt and Reeves emerged from “this little cafeteria place,” Cambria continues. “This was long before cell phones, so I was at the corner payphone [on the line] with my secretary. I see Larry and Gene coming up the street and I hear ‘pop pop pop’ and down they go. Reeves is rolling around holding his shoulder. Larry was laying on the ground with basically his abdomen open from being shot.”

“An ambulance came, and I helped put him in the ambulance. We get to the local hospital and Larry is laying there conscious. And there are just nurses there, no doctor. Larry says, ‘Shouldn’t you put the [IV] in me, the bottle by the side?’”

Cambria remembers he saw an operating room and opened the door shouting, “There’s a gun victim here!”

“The doctor was operating, and he’s yelling ‘security! security!’ But he came out and did his thing and that saved Larry’s life,” Cambria tells XBIZ. “They gave him about a 10 percent chance, but he made it.”

Flynt was then transferred to Atlanta in an attempt to stop his internal bleeding.

“Jimmy Carter’s sister, the minister, shows up,” Cambria laughs. “And she grabs Fehringer and me and says, ‘Join hands, and we’re gonna pray for Larry.’ And I look at Fehringer like, ‘Is this shit really happening?’”

Gene Reeves also survived the assasination attempt. “He lived to be 92. Larry paid all of his medicals and subsidized him for years,” Cambria says.

Flynt’s description of his ordeal during those March days in Georgia, as doctors attempted to stop him from bleeding to death, and then from succumbing to a hospital infection, is harrowing. The bullets had not severed his spinal cord; the injury instead prevented him from moving his legs while still feeling all of the pain.

“From the time I had regained consciousness, I’d felt as though my lower extremities were immersed in boiling water 24 hours a day,” Flynt later recalled.

A level of physical pain most people could not fathom, much less tolerate, would become Flynt’s reality for years to come.

Moving to Los Angeles

Flynt had been pondering a move to Los Angeles for some time and the assassination attempt hastened the preparations.

For two months in 1978, Flynt had his physical rehabilitation in Inglewood, in South L.A., suffering from excruciating pain and drifting away from the Christian mindset. Flynt’s memoir makes it clear that the months after the shooting profoundly affected his entire outlook on life and he returned to his initial skepticism about religion.

The Flynts eventually moved into a Mediterranean mansion originally built for Erroll Flynn, where Larry could “retreat into the dark confines of my bedroom, hunker down, and get through the day,” as he once described it, while Leasure, who had turned 25, took over the day-to-day management of the Flynt enterprise.

On March 5, 1979, on the eve of the first anniversary of his shooting, Flynt told a visiting reporter that even though the Lawrenceville judge declared a mistrial following the assassination attempt, he was ready to shortly return to Atlanta to face obscenity charges.

By the time Flynt arrived in Atlanta, though, his anxiety about another attempt on his life started growing. “We’re taking security precautions we didn’t take before,” he told the press. “Let’s face it, when someone’s running around who shot you, you have to look over your shoulder a bit.”

From then on, a small army of guards became one of the constants in Flynt’s daily life.

The Supreme Court

When Hustler had first launched, Flynt felt competitive towards Hugh Hefner and Bob Guccione. The first anniversary issue of Hustler in 1975 featured on the cover a superheroine, representing the magazine, stomping with her high heels over a hare (aka the Playboy Bunny) and a turtle wearing the distinctive Penthouse key necklace.

XBIZ reminded Mr. Flynt of his mid-’70s satirical attacks against Hefner and Guccione, and wondered if he needs to taste his competitors’ blood to get motivated to achieve at the level he has. But he had a much simpler explanation.

“I was just poking fun at them,” he said, sheepishly. “Trying to get under their skin, you know. Guccione and Hef would always try to ignore me. Thinking that if they ignored me, I’d go away. But I didn’t, you know.”

So the threeway rivalry wasn’t one of the engines of his success?

“I guess that’s the way it turned out,” Mr. Flynt said, before changing the subject.

It is not widely known, but it was Flynt’s ribbing of Guccione and his girlfriend, later his wife and co-publisher Kathy Keeton, that landed him his first appearance in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1976, as he was riding high on fame, Flynt encountered Keeton on a late-night talk show panel to discuss obscenity. Keeton explained later that she didn’t recognize Flynt. The Hustler publisher was in one of his moods that night and he lambasted her on- and off-air.

Shortly after, Flynt commissioned a series of articles and cartoons lampooning the Penthouse royal couple. Guccione and Keeton sued separately: he, on the grounds that Flynt had suggested he engaged in homosexual activity, and she because Flynt had printed a cartoon suggesting she had contracted a venereal disease from Guccione.

Guccione sued first in Ohio and Flynt lost, but the judgement, almost $40 million, was reversed on appeal. Keeton attempted to sue Flynt in Ohio as well, but the statute of limitations had run out. The only state that had a six-year statute of limitation was New Hampshire so Keeton tried to sue there.

Since Keeton was based in New York while Flynt was based in Los Angeles and Hustler kept offices in Ohio, the New Hampshire district court dismissed the case due to lack of jurisdiction. She tried the federal appeals court, which upheld the lack of jurisdiction ruling. So she carried her appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Flynt couldn’t miss the chance to represent himself before the Supreme Court, and he requested to do that. The Supreme Court disregarded his offer and appointed a lawyer for him.

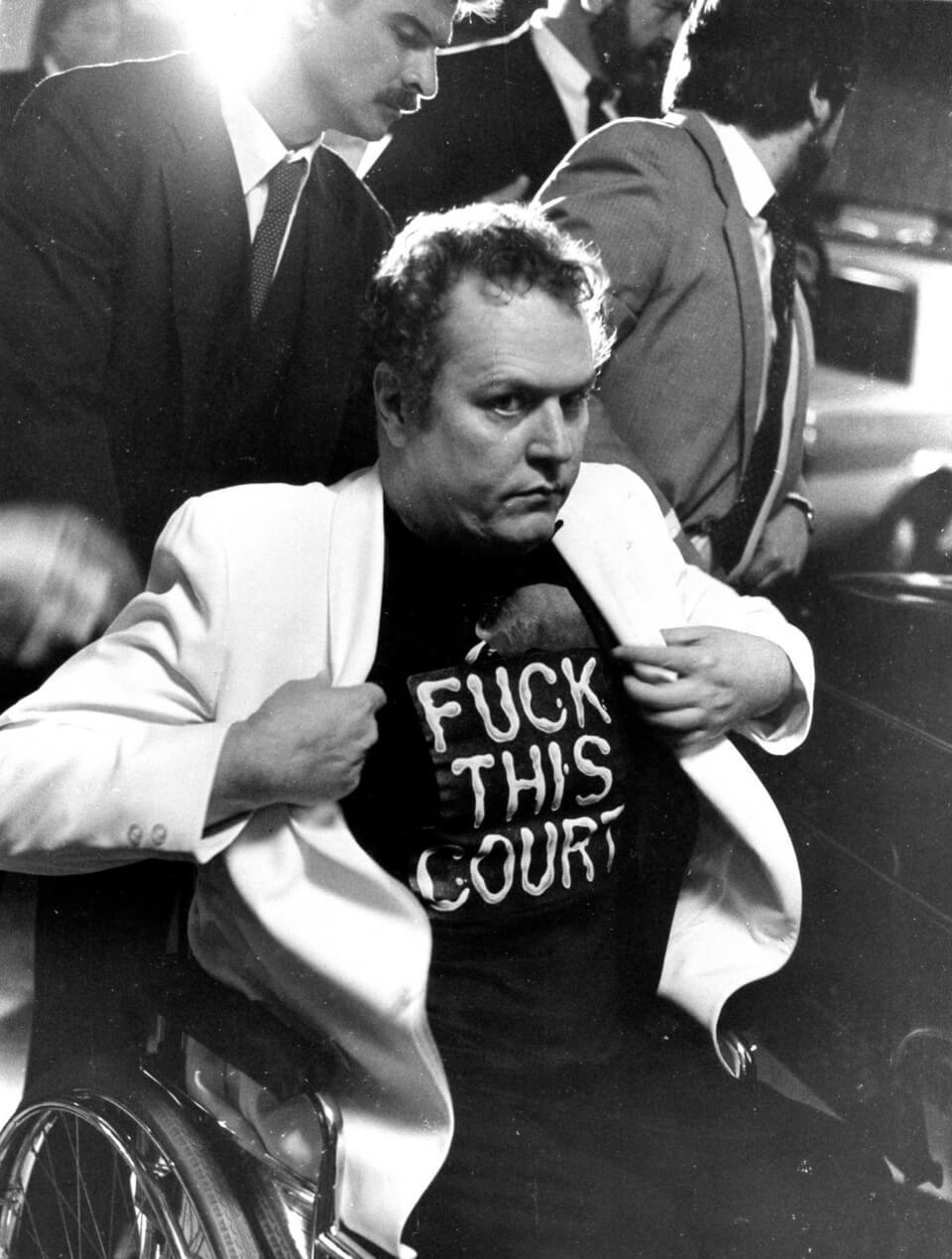

Flynt showed up in D.C. with a large entourage, riding in a small fleet of limousines flying small American flags like presidents and heads of state. Once in the courtroom, he kept attempting to intervene in the proceeding, but was ignored as his court-appointed lawyer — his second, whom Flynt had never met — argued his case.

The lawyer who had been hastily called as the first choice, a Yale law professor, withdrew when she learned Flynt had sent Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who had recently been appointed by President Ronald Reagan and was the first woman to serve on the court, an unsolicited subscription to Hustler.

O’Connor’s office had written to Flynt rejecting the subscription, with Flynt replying, “I’ll take you off my subscription list when you resign from the court.”

This was not merely a cheeky stunt. “If she’s so offended by what I represent,” Flynt told the press, “how can she be unbiased about any case involving me?”

The day of the hearing, as soon as Chief Justice Warren Burger, an appointee of President Richard Nixon, adjourned the court, Flynt loudly subjected all nine justices to verbal assault.

A visibly angry Chief Justice Burger ordered his arrest immediately, and the Supreme Court bailiff wheeled Flynt out to the rarely used Supreme Court holding cell. Since there were no handicapped bathrooms in the building, Flynt somehow persuaded the police to transfer him to a nearby hospital in his own fleet of limos.

After Flynt used the hospital restroom, the limos headed to the D.C. courthouse to arraign him for disrupting the Supreme Court. At the holding cell, Flynt unveiled the T-shirt he had had printed for the occasion, reading “Fuck This Court” in a font that resembled semen.

According to Flynt, many misread the shirt’s sentiment as applying to all courts – the word “this” on the shirt was meant to specifically insult “this” incarnation of the Supreme Court, led by Justice Burger.

Eventually, the Burger Court upheld the jurisdictional ruling of the lower court, which Flynt has described as a partial victory.

Jerry Falwell vs. Larry Flynt

A quality that marked Hustler as a product of the mid-1970s, as opposed to Playboy (mid-’50s) and Penthouse (late-’60s) was its obsession with parodies. Hustler had wide-open beaver shots, sure, but from its inception it was also an outlet for satirical humor in the vein of Mad Magazine, the National Lampoon and their TV counterpart, “Saturday Night Live.”

This meant that Flynt was (and still is) partial to parody ads where popular advertisements are tweaked to refer to topical issues in politics or society.

In the early 1980s, European liquor company Campari had launched a print ad campaign where celebrities talked about their “first time” drinking the company’s signature red herbal apéritif, but obviously playing with the double-entendre of their sexual initiation.

Never failing to seize publicity, Hustler lampooned the ads in their November 1983 issue, replacing the celebrity with media-savvy evangelist and right-wing politician Jerry Falwell.

“My first time was in an outhouse outside Lynchburg, Virginia,” the satirical interview text had Falwell say. “Wasn’t it a little cramped?” the parody ad mused, to which the caricatured Falwell replied, “Not after I kicked the goat out.” After continued banter throughout the full page ad, it ended with the punchline that Falwell’s “first time” was with his own mother.

Broad-stroked as it was, the spoof was clearly a First Amendment-protected satire of a public figure. Small print at the bottom literally read: “Ad parody — not to be taken seriously.”

But that’s not how Falwell saw it.

After a reporter showed it to him, he sent one of his associates to bring it to his Lynchburg, Virginia headquarters. First, he was offended because he thought someone had appropriated his image to sell the Campari apéritif.

“Since I became a Christian in 1952,” Falwell later informed the court, “I have been and am a teetotaler.”

But then he read the copy.

“I have never been as angry as I was at the moment,” Falwell testified later. “I felt like weeping.” He also hired Bob Guccione’s lawyer, Norman Roy Grutman, to present his case.

Falwell had met Grutman when the lawyer had represented Penthouse against the Moral Majority founder in an earlier lawsuit. Penthouse had published an interview with Falwell they had picked up from a freelancer, and Falwell argued that his words shouldn’t be published in the men’s magazine without his authorization.

The judge ruled in favor of Penthouse, pointing out that people who “invite attention and publicity by their own voluntary actions” were not subject to First Amendment exceptions.

Flynt picked a Los Angeles attorney named Alan Isaacman to argue against Grutman, a New Yorker, in a courtroom in Roanoke, Virginia — “Falwell country.”

At the trial, Isaacman asked Flynt to explain his reasoning behind publishing the Campari ad.

“Well,” Flynt testified, “we wanted to poke fun at Campari for their advertisements and the innuendos in them. Their ad copy left the question open: Were people talking about their first sexual experience or the first time they drank Campari?”

“To make the ad funny,” he continued, “we needed to have a person that was the complete opposite of what you would expect. If I had been featured in the ad, the parody would not have worked. But if someone like Reverend Falwell is in it, it is very obvious that he wouldn’t do any of those things, that they are not true, that it’s not to be taken seriously.”

The Roanoke jury ruled that Flynt was correct that nobody would have interpreted the parody Campari ad as literally saying Falwell was a “motherfucker.”

But it also ruled that Flynt had deliberately “inflicted emotional distress” on Falwell and “offended generally accepted standards of decency.”

Flynt and Isaacson immediately appealed the ruling before the federal Fourth Circuit.

On August 5, 1986, the court of appeals upheld the lower court’s decision, on a split 6-5 vote.

It was time to go back to the Supreme Court and face the top jurists Flynt had verbally assaulted.

The First Amendment

On March 20, 1987, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Flynt’s appeal. The court’s composition and leadership had changed in the interim and the Burger Court had become the Rehnquist Court.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist had previously ruled often against the press on First Amendment hearings. The mainstream press now realized that this review of the Fourth Circuit’s opinion could overturn long-held freedom of speech protections. Flynt now received the support of the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Virginia Press Association, the ACLU, major book publishers, pretty much every editorial cartoonist, and many others.

Oral arguments were scheduled for December 2, 1987.

Alan Isaacson’s argument in favor of the First Amendment on December 2, 1987 is, verbatim, the rousing climax of “The People vs. Larry Flynt” movie.

The late Justice Stevens, an old-school liberal and champion of civil rights and freedom of speech, gave Isaacman the chance to explain what “the public interest” was in lampooning Falwell.

Isaacman hit a home run.

“There is public interest in having Hustler express its view that what Jerry Falwell says, as the ad parody indicates — is B.S.,” the lawyer argued. “And Hustler has every right to say that somebody who’s out there campaigning against it, saying ‘don’t read [their] magazine and [they] are poison on the minds of America and don’t fornicate and don’t drink liquor’ — Hustler has every right to say that man is full of B.S. And that is what this ad parody says. It put him in a ridiculous setting. Instead of Jerry Falwell speaking from the television with a beatific look on his face and a Bible in his hand, Hustler is saying, ‘Let’s deflate this stuffed shirt; let’s bring him down to our level.’”

The Supreme Court took a year to publish its decision, and on February 24, 1988, it unanimously ruled in favor of Hustler Magazine and Larry C. Flynt, with the Chief Justice writing in the decision that “the fact that society might find speech offensive is not a sufficient reason for suppressing it.”

The decision was, in the words of legal observers, a triumphant celebration of freedom of speech.

After years of fighting against all odds, and harder than anyone in the business, Larry Flynt became inarguably the man who had the most profound impact on free speech and freedom of expression for the adult industry.

Mr. Flynt has proudly called it “without question my most important battle.”

“I sincerely hope that this victory over censorship signals the swing of the pendulum back toward a more open society,” Flynt wrote in his editorial for the July 1988 issue of Hustler, “where sexual communication can be conducted freely and with an accompanying honesty.”

“Those traits,” he continued, “have been sorely lacking in our initial approaches to the AIDS crisis and sex education, and their absence hinders people’s ability to make informed decisions about disease prevention, contraception and abortion. Hustler has always promoted the concept that sexual openness requires sexual responsibility, just as maintaining our civil freedoms requires the responsible effort to vote, pay taxes and obey the laws and legal precedents of the land. I am very happy to have helped ensure that one of those precedents guarantees every American the right to make fun, particularly of those people who try to hold themselves above the rest of the world.”

To this day, industry pioneers extoll Flynt for his efforts on behalf of the whole community.

“It’s because of Larry that we have a modern-day adult industry,” comments Doc Johnson’s Ron Braverman. “And it’s because of Larry, and his efforts in supporting the First Amendment and free speech that we have a lot of freedoms we have today.”

During the XBIZ interview, when asked if he ever wished he could concentrate just on business and not on these epic lawsuits, Mr. Flynt explains that he was always quick to defend himself in a lawsuit.

“Over the years, I’ve won most of them. Or kept [the losses] down to very low,” he says.

Physical and Cultural Rehabilitation

As the eventful 1980s came to a close and in the wake of Leasure’s unexpected passing, Flynt regained focus and energy by undergoing treatment to ease his pain. The surgeries allowed him to phase out the painkillers and his passion for work returned with a new clarity of purpose.

Flynt began to expand his publishing business and purchased the Larry Flynt Publications headquarters in Beverly Hills, decorating the offices lavishly.

Remarking upon his taste for posh furnishings, Mr. Flynt has said, “I don’t know much about antiques, but I know what I want.” And he certainly does as evidenced by the columns, carpeted floors, oil paintings — originals and reproductions — statues and baroque furniture.

This is the office where “Larry Flynt” — publicity-seeking troublemaker — had his metamorphosis into “Mr. Flynt” — Beverly Hills businessman.

During this period, Flynt started appearing in public with a new romantic interest. He had fallen for one of his nurses, Liz Berrios, a stylish, smart, no-nonsense Los Angeles native. He gave her a red Faberge-egg locket with their pictures to wear around her neck.

Joining Flynt’s cadre of trusted confidants, Berrios also began taking leadership roles in LFP and the Hustler organization.

Berrios was fundamental in helping Flynt shape up for an upcoming life-changing chapter of his journey.

“I’m happy that Larry met Liz,” Kenny Guarino tells XBIZ. “I admire her for her loyalty in keeping him healthy and working with him in his numerous endeavors.”

In the mid-’90s, Flynt and a literary agent put together his autobiography, “An Unseemly Man.” The memoir attempted a difficult feat: to rebrand Flynt in the public consciousness as a First Amendment hero.

But what the American people really needed to finally see the outrageous 1970s pornographer in a different light was a Hollywood biopic.

“The People vs. Larry Flynt”

In 1993, screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski took a Flynt biopic pitch to Columbia and director Oliver Stone, who saw Flynt as “the late 20th-century version of Horatio Alger pursuing the American Dream, but with the perverse twist of building his empire from pornography.”

The screenwriters did their homework and when they finally went to the man himself to get his blessing, Flynt said what every biographer wants to hear: “I don’t think anybody in the world could’ve written a better movie about me than you guys.”

However, Stone suddenly became unavailable to direct and the screenwriters lobbied for acclaimed Czech-American director Miloš Forman for the project.

Forman has described himself as a terrible fit for the project. “I am definitely one of those old-fashioned, small-town people who was conditioned, in my childhood in Czechoslovakia, to think that pornography is bad and — I am afraid — I shall never be able to shake off that notion.”

Upon reading the Alexander-Karaszewski script, though, Forman was riveted. A survivor of both the Nazi occupation and the Soviet takeover of his birth country, Forman has stated that he believes authoritarian regimes start with “crusades against those they [classify] as perverts: pornographers, homosexuals, Jews and blacks.”

As censorship encroaches, Forman thought, the list of dangerous “thought criminals” grows and grows until it encompasses Shakespeare, Jesus Christ and, finally, “any plumber, teacher or housewife who [does] not conform to the official ideology.” Under such regimes, everyone, eventually, becomes a “pervert.”

Flynt annotated the script for Forman. “He was reciting his remarks and I was just making notes feverishly on the margins of the screenplay, until the moment Flynt turned the last page and he broke off,” the director later reminisced.

Forman mustered up his courage and asked Flynt if he minded the fact that he didn’t look like a hero in some of the scenes.

“Of course I do!” Flynt replied. “Yes, I do mind — but what can I do about it when it’s true?’”

Flynt wanted Michael Douglas to play him, and the producers considered Tom Hanks and Bill Murray, but when Woody Harrelson was approached, it soon became evident the fit was flawless.

“Both of us were poor white trash who somehow got a leg up in the world,” Harrelson said.

Flynt and Harrelson hit it off famously. The publisher even lent the one-and-only 14-karat-gold-plated wheelchair, a gift from Leasure, for Harrelson to use in the film.

“Larry Flynt is a devil with angel’s wings,” Forman said, again and again, about his protagonist. “Half the man is just sleaze and smut, but the other half is noble and admirable. That’s confusing, and because it’s confusing it’s very intriguing.”

The film was shot mostly in Memphis, Tennessee, over 74 days and was ready to be screened by October 1996.

“The movie is frighteningly real,” Flynt told the press the day after Forman showed him the film for the first time.

XBIZ asked Mr. Flynt if he thought public perception of him changed after the movie was released.

“Well, they were able to put my life in a fuller context,” he reflects. “I think people got a better understanding.”

Susan Colvin of CalExotics expresses, “It’s wonderful that people have come to realize that Larry isn’t an extremist, he is an average person who stood up for the First Amendment and is passionate about people’s rights. This is someone to look up to.”

She adds, “There’s much more to Larry than the fact that he was shot. Larry truly believes in the First Amendment, and not only for adult businesses. Larry helps a lot of people. A lot of people who’ve had problems, he helped them with their lives, he’s supported them. And he never talks about that.”

Although Flynt has not seen the film in over a decade XBIZ asked him what part touched him the most, what moment he felt the filmmakers captured particularly right.

“When I was shot,” he replies, after a long silence. “It definitely had an impact on me.”

One person who was also affected by the shooting scene was Paul Cambria, but for different reasons.

Cambria had long stopped working for Flynt, but one day in the 1990s the lawyer got a call.

“I pick up the phone and I hear ‘Hi Paul…,’” Cambria tells XBIZ. “’Larry?’ I say. ‘I’m fixin’ to get arrested in Cincinnati for selling my magazine and I want you to represent me.’”

“I hadn’t seen him in eight or nine years. When I saw him again,” the attorney says, “he started crying.”

He remembers Flynt telling him, “By the way, they’re making a movie about me. And you might get upset with how they made the lawyer character.”

“In the movie Isaacman gets the credit for saving Larry’s life!” a still-annoyed Cambria tells XBIZ. “He’s a civil lawyer! Isaacman didn’t know him at the time of the shooting, and he didn’t get shot!”

Edward Norton plays Isaacman as Flynt’s main attorney for several cases when in fact Flynt has always retained many lawyers. This results in the film’s Isaacman being the lawyer shot alongside Flynt in Lawrenceville, instead of Gene Reeves. Cambria was completely written out of the incident.

“The People vs. Larry Flynt” opened at the New York Film Festival in October 1996. Flynt flew to the premiere were he was photographed in a loving embrace with a beaming Woody Harrelson and Courtney Love, who played Leasure.

The New York Times gave their verdict, and it was poster-line ready: “A blazing, unlikely triumph.”

An Unexpected Friendship

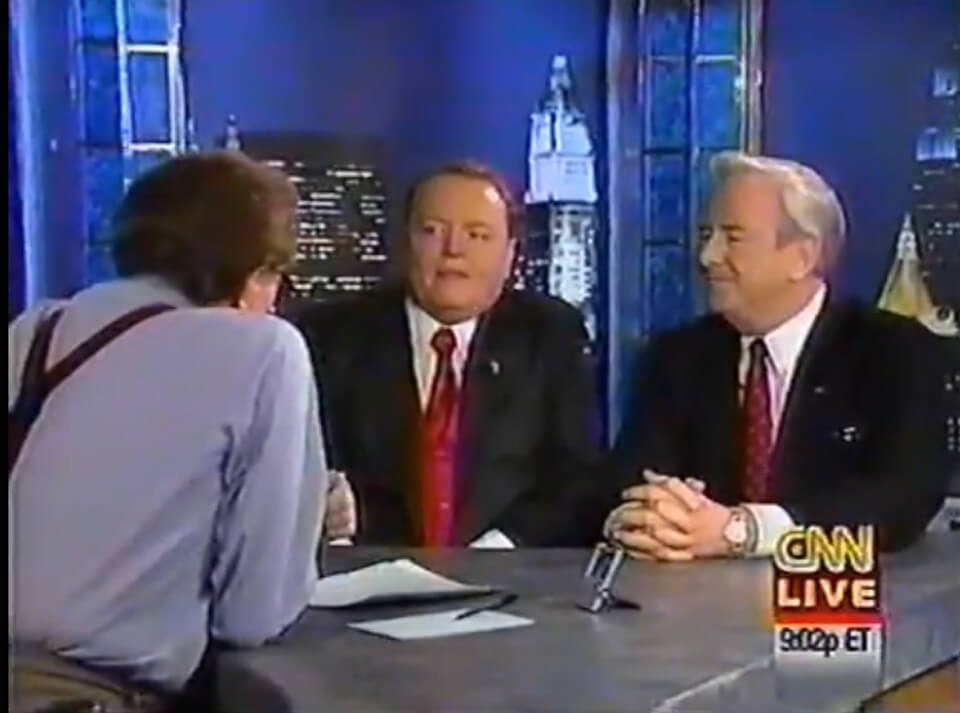

One odd result of “The People vs. Larry Flynt” was that eight years after the historic “Falwell vs. Flynt” Supreme Court decision, CNN interviewer Larry King managed to bring together both men on his show for a chummy debate.

Falwell refused to see the movie, but nevertheless told the press that “there’s no question that this movie is inaccurate.”

The evangelist hugged the pornographer in front of millions of viewers, even though, as Flynt wrote years later, not only had they been “archenemies for 15 years” but their respective beliefs “traveled in different solar systems.”

It was the first time since the 1988 verdict that the two men were in a room together.

“I disagreed with Falwell on absolutely everything he preached,” Flynt later commented, “and he looked at me as symbolic of all the social ills that a society can possibly have. But I’d do anything to sell the book and the film, and Falwell would do anything to preach, so King’s audience of eight million viewers was all the incentive either of us needed to bring us together.”

Even while fighting in court, Flynt had always had a soft spot for Falwell, whom he saw as a fellow Southern good ol’ boy.

“Falwell was every bit as much a ‘hustler’ as I was,” Flynt stated, before they became friends, “frequently traveling with a large entourage, wearing expensive suits, and looking like a well-to-do corporate executive — which he was.”

Flynt’s mother had taught him that “no matter how repugnant you find a person, when you meet them face to face, you will always find something about them to like.”

Five days after the minister’s passing in 2007, Flynt penned a remembrance for the Los Angeles Times titled “My Friend, Jerry Falwell.”

Diversifying the Business

After the film’s release, it was time to get back to business. “I am as happy as I could possibly be considering everything that I’ve had to go through,” the 53-year-old Flynt said in 1996. “I’m at a point in my life where, [it’s like,] ‘What do I do for an encore?’”

A technological innovation was going to provide the answer to this ennui, in the form of the “Hustler Online” website, which would serve as the digital edition of the magazine.

When XBIZ asks if there was a moment when he realized the internet was going to change the magazine business forever, Mr. Flynt gives a philosophical answer.

“I think that was just a natural evolution, you know? Down through history, being a progressive nation — the industrial revolution, the computer revolution, it’s all the same to follow suit. But you have to adapt to that, you know?”

And adapt he did.

Sometime in the ‘90s, Mr. Flynt saw the writing on the wall. Men’s magazines — specifically, pictures of naked women, until then the signature product of the Hustler brand — were going to be rendered niche content by free internet porn.

“I knew that the advent of computers was going to change technology and publishing,” Mr. Flynt tells XBIZ. “All you had to do was stand by and see the change evolve. And you had to be there to take advantage of the progress it brings.”

Despite the ubiquity of internet porn, LFP continues publishing Hustler, Taboo and Barely Legal to a loyal readership. Mr. Flynt has further diversified his interests into the worlds of gambling, retail stores and brand licensing. And he crucially made the decision in the late ‘90s to start producing video content and licensing it for broadcast on cable and at hotels.

In 2012, he closed a deal to purchase pay-per-view distributor New Frontier Media for approximately $33 million, and soon Hustler’s broadcasting unit cemented its status as one of the leaders in a thriving market.

Other legacy adult brands were less nimble in reallocating resources, and they paid the price.

”Some people fall down to that trap, you know? You have to be much more aware of your surroundings,” Mr. Flynt tells XBIZ with a satisfied smile.

For Braverman, Flynt has always been and continues to be “a forward thinker. He’s fought beyond the current day and he’s always had the ability to change not only the way the business is, but the way it will be. People in the industry still keep an eye on what he’s doing to make their own moves. He’s someone who, when he makes certain decisions, people pay attention.”

In 2010, Flynt presided over the opening of an enormous, three-level nightclub called Larry Flynt’s Hustler Club in Las Vegas. Overseeing the revelries from the VIP Grand Honey Suite high up above the main stage, Flynt brought star power to the event, accompanied by adult star Lisa Ann – costumed as a lookalike of Sarah Palin, evoking her role in Hustler’s famed “Who’s Nailin’ Paylin” parody.

But many attendees just wanted to see the man himself.

“The people just love him!” friend and business associate Michael Warner tells XBIZ. “They know him as a fighter for the First Amendment. He fought the fights for everybody. I’ve been with him at restaurants where total strangers come and thank him for his First Amendment fights.”

As for Flynt’s multi-pronged approach to the industry, Susan Colvin tells XBIZ, “First of all, he’s brilliant. He looks at the world differently from most people, he sees the broad picture, whether it’s politics, the First Amendment or how a business should be run.”

She continues, “Their stores buy CalExotics products — they do a great job, they even put our products in their casinos. They have been enormously supportive. He comes up with a lot of plans, and they’re all smart, and more importantly, viable.”

Like Warner, she praises Flynt’s character. “When he gives you his word, he keeps his word,” she says. “When he’s your friend, he’s your friend. In the good times and the bad.”

Longtime industry insider Kenny Guarino agrees that Flynt deftly navigates an often cut-throat business with honesty.

“Larry is a true renaissance man,” he tells XBIZ, “innovative and with a unique ability to interpret the changing norms and attitudes towards the adult industry.” Guarino also credits Flynt’s integrity with his success in a business that has seen many colorful characters of diverse reliability. “Larry has always been a good businessman and an excellent negotiator. Most importantly, however, Larry Flynt is an honorable man to work with and engage in business deals.”

Beyond Hustler’s expansion within traditional adult entertainment, gambling has become increasingly important for the 21st-century version of the company.

“Had I known that casinos would be as lucrative as they were,” Flynt has told the press, “I would have gotten into them long before I did.”

The casinos are not merely a business investment. Flynt is a lifelong fan of games of skill and chance and has made a name for himself as a skilled player in the worlds of high-stakes blackjack and poker, to the point that trade magazine Card Player described him as “a Master of Stud.”

Reflecting on Mr. Flynt’s decades-long ascent, Cambria recalls, “When he started off, he didn’t have a five grand retainer. Now he’s worth close to one billion dollars. One day, a check dropped out of his pocket, and I hid it from him as a joke. It was for $250,000 from some casino.”

Another area of rapid growth is the Hustler retail operation.

As shoppers started migrating to online superstores for their basic needs, Flynt gambled on people, especially women and couples, who wanted a “female-friendly” experience when shopping for intimacy items.

“I’m more of a traditional bricks-and-mortar guy,” he told the press.

Five years ago, Flynt started planning a dramatic expansion of the Hustler Hollywood retail chain, especially in counties with cheaper real estate and areas that were less likely to shop online.

“Our biggest challenge, believe it or not, is zoning,” Cambria tells XBIZ. “Getting stores located in desirable places and have them not be classified as adult and [forced into] industrial sections. We want to locate them in malls and in major intersections. We keep fighting those laws. Larry has 40 stores in very good places.”

“In the old days it used to be obscenity, and now it’s zoning,” says Cambria.

Flynt the Feminist

Answering the feminists who have picketed Hustler over the years, Mr. Flynt has always replied that he cannot possibly be a misogynist because he loves women.

The offices of LFP attest to this. The ratio of men to women, even in managerial positions, is weighed in the opposite direction from most business operations its size.

His wife Liz Berrios oversees everything from an office right next to her husband and his daughter, Theresa Flynt, has played various key roles in the business, including creating the Hustler Hollywood retail chain.

“What impressed me most when I joined the company,” in-house publicist Minda Gowen tells XBIZ, “was not only the diversity within all our divisions but that Larry Flynt had many women in positions of power. Looking around at his executive table in the boardroom, I pinched myself when I realized I was one of them. Coming from the mainstream entertainment industry, this was the thing that most surprised me.”

“The heads of our magazines are all women,” Gowen continues. “The head of HR, our in-house counsel, the head of marketing for our casinos — all women. I was told from the beginning that Larry Flynt didn’t care what a person looked like, what their age was or their sexual orientation, as long as they can do their job and steer the company in the right direction. That’s what matters the most to him.”

The Modern Hustler Brand

For the adult industry at large, Flynt’s legacy is shaped by what he has created and how he has weathered many storms over four decades.

“When you say ‘Larry Flynt,’ I think not only about keeping a business viable but also about how you pivot over so many years and so much change,” says XBIZ publisher Alec Helmy. “He’s always been multifaceted, to a degree that no one has ever matched.”

“Flynt is to the adult industry what KISS is to rock music,” Helmy continues. “KISS is a brand that transcends its music. The combination of kabuki-inspired makeup, the stage show, the fire, explosions, make KISS exponentially bigger. The magnitude and extent to which Flynt has grown and diversified his business, as well as the seismic legal battles he’s won, make him an all-time heavyweight champion.”

Paul Cambria agrees. “That’s the thing with Larry. He doesn’t slow down at all.”

Still a Freedom Fighter

During these past two decades of business growth and diversification, Flynt has still very much remained a tireless political crusader, fighting against moral hypocrisy.

In late 1998, Bill Clinton was well on the way to being impeached for the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal and removed from office after easily winning re-election two years prior.

Flynt stepped in with one of his $1 million offers for anyone with information that would show sexual hypocrisy on the part of the Republican politicians leading the impeachment proceedings against Clinton.

The main House impeacher and Clinton nemesis, Newt Gingrich, had resigned from the Speakership in November 1998 under ethical suspicions. The GOP caucus then voted unanimously for Bob Livingston, an obscure congressman from Louisiana.

Yet, on the same day the House was scheduled to vote on the impeachment, Livingstone revealed he would not assume the Speakership. Flynt, it turns out, had unearthed evidence that the married Livingston had been involved with at least four other women during the previous decade.

Today on Mr. Flynt’s desk, behind a plaque that reads “Everyday I’m hustlin’,” there’s a framed portrait of him and his wife with Bill Clinton.

A lifelong reader of history books, especially about his beloved America, Flynt had now secured his place in them, the same way his victory over Falwell had secured his place in the law books.

The personal and the political are two sides of the same coin for Flynt. He has authored three non-fiction books on the intersection of these two areas. The most recent, 2011’s “One Nation Under Sex,” co-written with scholar David Eisenbach, is especially dear to Mr. Flynt, who tells XBIZ he thinks it is his best book.

During Reagan’s heyday, Flynt said that “parody has become so real that we’re gonna stop doing parody.”

Of George W. Bush he said at a 2010 lecture, that his legacy “will not be Afghanistan, Iraq or even Hurricane Katrina. It’s going to be those two toadies [John Roberts and Samuel Alito] he put on the Supreme Court. In the next 25 to 30 years, they’re going to be spewing their conservative philosophy to the whole world.”

And in his editorial for the December 2019 issue of Hustler, written a few weeks before the House voted to impeach Donald Trump, he explained that while he had offered a $10 million reward for information leading to the impeachment of the president, it “didn’t uncover a smoking gun at that time.”

Flynt, however, remains bullish that one will be found in Trump’s long-hidden tax returns.

XBIZ asks Mr. Flynt what his thoughts are about the strange alliance between his socially conservative enemies, the self-appointed moralists of America, and someone like Donald Trump, who in many ways – involvement with casinos, adult stars, fondness for opulence, licensing his brand name, boisterous public displays and so on – shares parallels with the Hustler publisher.

Mr. Flynt ponders the notion.

“This country has got to develop so people stop feeling guilty over the concept of obscenity and sin, because it defies definition,” he says. “Repression, you know, just makes certain types of behavior more popular. I guess you could say [enjoying] pornography is one of them.”

He “sees some truth” in the paradox that the more repressive society gets, the more money the adult industry can potentially make.

Mr. Flynt then takes a long pause and what he says next is unlike his oft-repeated witticisms.

“We can’t be afraid to be free,” he asserts, underscoring how freedom means tolerating even those viewpoints we may vehemently oppose or wish to see suppressed.

And then he gives us one for the ages:

“A lot of people are afraid to be free.”